Taj time!

Shadow play

I knew it would be hard to leave New Orleans to begin graduate school in Savannah. I also knew that my love for getaways, festivals, and camping would continue to grow with my new surrounding geography (and a more flexible school schedule). So, in February of 2022 I purchased a campervan!

I did my research by renting a campervan and doing the most amazing Pacific Northwest trip with my best friend — (copy our trip here)! I LOVED the experience of traversing landscapes, keeping my belongings on me, and the freedom of exploration.

Over a few month, I spent some time customizing my van. Primarily, building out new woodworking and theming the van into a cotton-candy pastel paradise. ‘Poof the Pastel Puffer’ took shape and we hit the road in July to rack up 10,000 miles of adventures before I started at SCAD that fall. We’re now on 30,000 miles and counting!

Working on the van taught me so much about efficiency planning. While it often felt like 3-steps-forward, 2-steps-backward, I have never loved anything more. A couple of my top tips:

Make it modular — this modular “grid wall panel” setup allows me to clip in storage without heavy cabinetry and also allows me to strip down to a more aesthetic wall when I’m not doing a long haul.

Prioritize projects — I would have loved to paint my mural ceiling and add my dream light switch, but putting in the blackout curtains and situating the shelf storage was far more important before pushing off!

Experience the van while working on it — I extended the bed out when my friend joined me in the van for the Louisiana Migratory Birding Festival. That’s when I realized I set the table height wrong, preventing me from accessing my clothing stored underneath. It was frustrating to redo the table installation but necessary.

Lean on friends — so many awesome, talented friends helped me out by lending power tools and expertise. Attaching curtains with industrial velcro and bungee-ing my under-table storage cubes were perfect last-minute fixes when working on a limited timeframe

Make it home — the theming I did to make Poof my happy place delights me every time. The extra hours hand-painting clouds on shelving and staple-gunning cut-up fuzzy blankets were so worth it.

If you want to understand the DEEPEST parts of my spatial planning brain, check out this snapshot of my Google Maps. THIS is why I was an Urban Studies major at Columbia, and why I am so drawn to optimizing lived experiences.

Trip planning for a few days on the road! Some city stretches on the upper left. On the bottom right, Shenandoah pins point to campsites, vineyards, and trailheads at my fitness level (no 10 mile hikes please!).

Laying out a pit-stop in Pittsburgh. I love that these Google Maps listings lets me estimate distance, cost, ambiance, and menu before I select where to go to next! I can easily take recommendations out from text messages onto a mapped visual.

The chaos that ensues when I live someplace!

I have spent a lot of time researching trips/cities, and it would delight me if others would benefit from these efforts.

Some of these are several years old, so do double check these places are still open. Check out some of the trips I’ve planned in the past, below, and reach out if you have any questions or feedback!

Below is a section that shares more about my experience studying abroad in India, Brazil, and South Africa. While not part of more recent van life experiences and odysseys, I think it is an earlier glimpse into my draw to community, sense of adventure, and love for academia.

The IHP Comparative Cities program sends Urban Studies majors to spend 5-weeks each in Ahmedabad, India; São Paulo, Brazil; and Cape Town, South Africa. In each location, we complete independent research and engage in homestays.

The academic curriculum is combined with fieldwork involving key actors and stakeholders — public agencies, planners, elected officials, NGOs, and grassroots organizations. We spend time in different cities across the globe to better understand the interconnected social, physical, economic, environmental, and political systems affecting urban environments.

Though human needs may be similar around the globe, why does a city's ability to satisfy those needs vary?

How do people create a sense of place, of community, of urban identity?

What historical and sociocultural contexts frame the opportunities, constraints, and uncertainties of urban life?

What must be done — and by whom — to move toward ecologically sustainable cities?

What are the opportunities for political action by individuals, community organizations, social movements, and local governments to shape city life?

On the active Tumblr I have posted videos and images collected from my travels, quotations from interviews, blog posts, as well as post a series of podcasts from the field.

Shadow play

One more that’s it for now I promise

(Thanks, Taku!)

Delhi Sunday Crew picture

Ceilings to heaven, Qutb Minar

Moi feat marble

Taj time!

Humayun’s tomb

Letter home:

I’m writing (read: dictating. Sorry for typos) this email from the steps of Gandhi’s ashram. This museum is quite unimpressive, but it’s left me with lots of time to sit and reflect until our group gathers in a half hour. Yesterday we had our first neighborhood day in India, this is different from our city walks, because we choose one of five neighborhood options to go visit as a small group and report back with a presentation to the larger group. Among the options were a bunch of areas that suffered in the wake of Indian and Pakistani relations, but I chose to visit and area on decline after textile mill shutdowns in the 1980s (because of my interest in adaptive reuse). From the options presented, it was quite clear that would be going to some very low income areas, often with very marginalized populations. I prepared for myself for the worst, anticipating an Indian version of the New England mill town narrative resulting in blight. And of course, from my preconceived notion, I thought we’d be visiting a slum. However, when we arrived it was quite clear that this is not the case.

We first were welcomed into one of the smaller textile factories that showed us the work that they are providing for women in the neighborhood. We then were invited into one of the local family’s homes, and were shocked by the beauty of the inside. Everything was covered in linoleum tiles and absolutely spotless, they brought out chairs from the back for each and every one of us and, slowly but surely, a gaggle of people from the community came forward, including so many children who wanted our ‘autographs’ and to take photos with us. Slightly uncomfortable, but we were the first foreigners many had ever encountered. We all sat around in the main living room, using a translator to ask them questions about the mill unions, university, and life/challenges in the neighborhood. A few of the students came over to the house and spoke to us in perfect English. One of the women, who was 21, told us that she like to do henna and her free time, and immediately sent her brother off to go get ink and proceeded to give us each hand henna tattoos. She then took us to her salon, which is around the corner and told us about how, since her cast was prevented from getting any loans from the bank, she borrowed money from her family and friends to build up their house and open a very successful start-up salon on the second floor.

The neighborhoods are so dense that the only option is to build up, so the amount of floors you have in your house is a huge status symbol and also allows you to bring in more family from the countryside to live in the city. Throughout the day, we were followed by a whole crowd of children, who were outgoing and friendly and wanted to answer all of our questions. When we are trying to figure out the relations of the people in the home, people kept saying “neighbor,” “neighbor,” “neighbor.” When we were hanging out on one of the terraces, they were eager to point out their own homes and were so filled with pride about their families and their community. It really warmed my heart, especially considering I went in expecting a super blighted and degraded neighborhood, only to see an incredibly vibrant community that maintains their formalized homes so perfectly. There weren’t enough hours in the day to go into all of the homes that we were invited into, and we even got to finish out the day with the round of cricket with a group of five of the kids who had been following us around all day.

A lot of the community resiliency I am sure developed because of their marginalized status (and with it and necessity for self-sufficiency and power in numbers), but it’s different to see how such a communal society compares to our individualistic one, their lives seem so rich and filled with love that it really caused me to question our western superiority complex.

The day before our visit we learned about the Indian caste system, which defines how the community is marginalized. The lecture was very eye-opening and disturbing, describing a self-perpetuating cycle of unbelievable degradation. The system only recognizes four levels of castes, the fifth of which are the Dalits (formerly called the untouchables). The Dalits have severe proscription of social mobility and are said to have been born impure and dirty, the only way to improve their condition is to conform to their caste and hope for an upgrade in the next life. They’re supposedly there because they either did something awful and their previous life as a human, or lived very successfully as an ant. The system itself is legitimized and perpetuated by religion, institutions (of family, marriage, education, law, and politics), legends, proverbs, attitudes, and language – people born in the lowest cast or given names that literally translate to ‘dust,’ 'garbage,’ or 'useless.’ It’s inescapable. To this day, there are unbelievable cases of abuse and discrimination of people from the lowest caste – including rapes, terrorism, and even brutal deaths. If a Dalit even crosses his shadow with somebody from an upper cast, they are considered to have polluted the higher level, and are subject to unfathomable beatings and punishments. Dalits must therefore live in separate enclaves of society, as to not pollute anyone else who may come in contact with them (like the neighborhood we went to), and, in colleges, even after affirmative action, they must sit and eat and separate sections of the dining hall.

I was very surprised to learn our neighborhood was Dalit. The experience overall really put the caste system into context for me, and I think was a really important thing to see in the first week in India. The whole system is so ridiculous, and the people there were so filled with love that it was hard to understand how they fit into the plagued and polluted division of that system. Also, it challenged my notion of what poverty in India looks like, because these families, despite having formalized homes, still had to have two parents working at all times just to make ends meet and put their children through school. They were established and prideful, but still struggling.

Several of the other groups witnessed unbelievably degraded conditions in their site visits, including a Muslim neighborhood that had a barbed wire wall built around the exterior and often had Hindus from the surrounding buildings throw bombs down into their area. Another, went to a refugee site for Bangladesh people, and explained the police brutality that that population encountered, including indentured servitude and terrorism such as waterboarding. A third described nonexistent municipal services, meaning sewage sat out in pools in the middle of the street. Clearly, there are ton of serious issues and tensions in India left to understand and grapple with.

We had a very intense emotional debrief after I finished writing the beginning of this email, at the ashram. I still feel very comfortable (maybe because my visit was more inspirational in the resilience of the human condition than depressing), but many are grappling with cultural shock and positionality. I’m not quite sure if it’s hit me that were here yet. I wonder when it will?

We luckily we have some amazing lecturers coming in to discuss topics with us. This past week we had a lecture on the history of Ahmedabad and Gandhi’s influence in the region on the textile mills by a Columbia grad and historian, Howard Spodek. We also had one on Indian politics, that describes the complex political dominance that emerged despite minority middle class via very strategic urban branding after the intense 2002 religious riots that tore through the city. Next week we will be going to site visits of labor and also have a panel discussion with several Indian academics on the topic of global circuits and labor. Our site coordinator, Sonal (who I mentioned last time) is super well connected here, she has an impressive army of helpers, translators, community leaders and intellectuals at her beckon call.

I’m wrapping up this email in my hotel, after a long walk through the neighborhood in which we encountered our regular crew – monkeys and cows. We had to go for a walk, because this whole week has been filled with the absolutely most delicious food you can imagine. I still haven’t bonded very well with our faculty fellow or traveling professors, but I feel really close to a lot of the people in our program, in fact – there’s not one person I don’t like. It’s really refreshing that nobody cares who or what is cool, we just are all really easy-going and adventurous, it’s a pretty spectacular group.

Last night, we were invited to an Indian wedding (one night out of a five night celebration with countless rituals), which was really fun and special, we got to listen to Indian music and participate in dancing with some members of their community. I was so tired afterward, that I managed to fall asleep in my rickshaw, which I believe must be some sort of symbol of my adjustment to the area. I surprised myself!

My bags are all packed up and I’m moving into my homestay in just a few hours with Aubrey. I’m really excited, but also nervous! It’s only 19 days, though (I cannot believe how quickly it is flying by).

The Red Fort, Agra, India

Baby Taj marble inlay details

Qutb Minar, Delhi

“You’re not sitting in traffic, you ARE traffic”

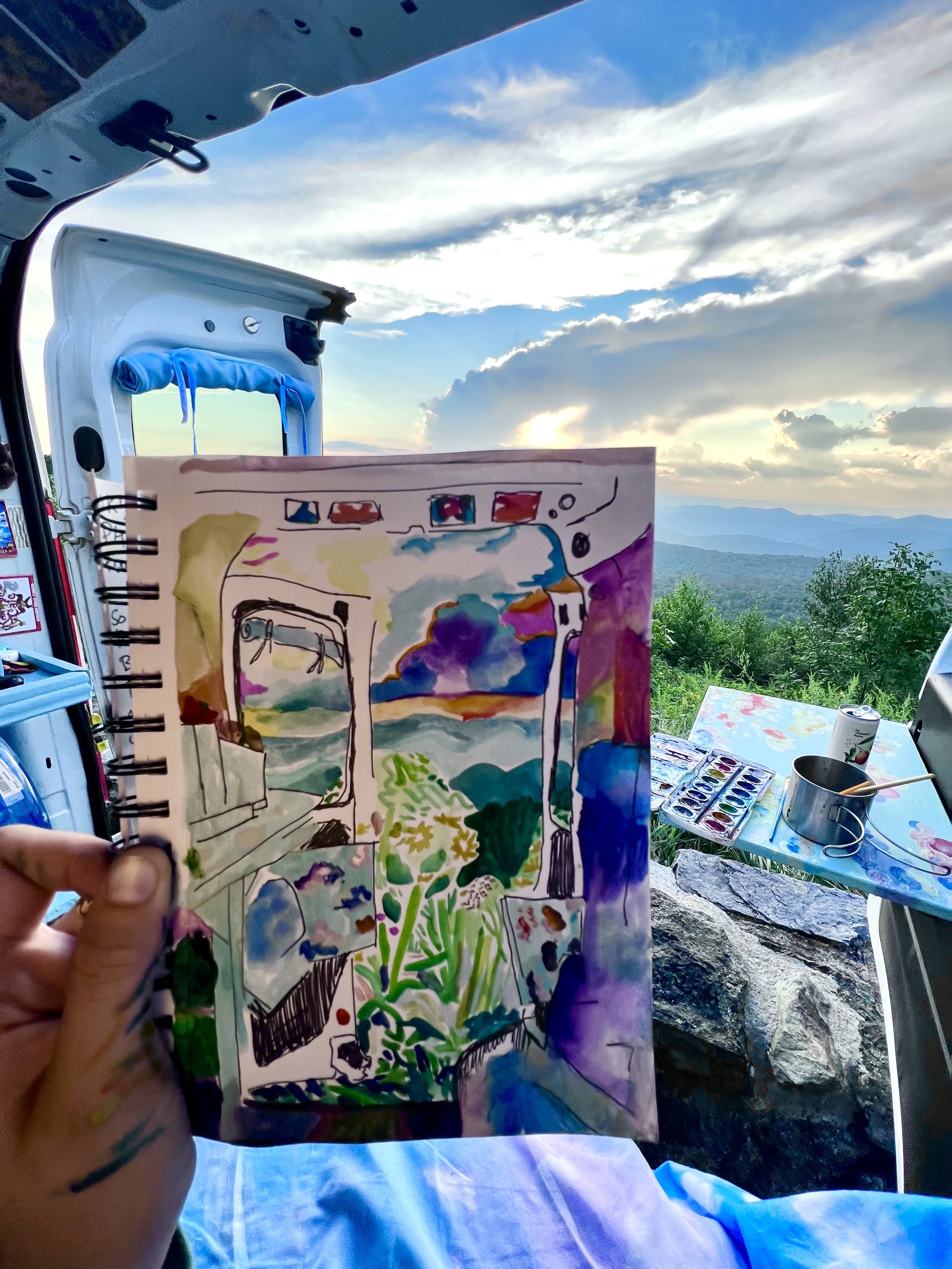

Exploring the wool craft markets with my trusty observation journal

My life is my message – MK Gandhi

Bhadra Plaza fort from 1411

Our commute home from class the other day!

Neighborhood vibes

Religious patterns