We had 2 hours to kill between our NYCHA site visit and our trip to the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Community Center, so we swung by the BK bridge

Jain temple in the Old City

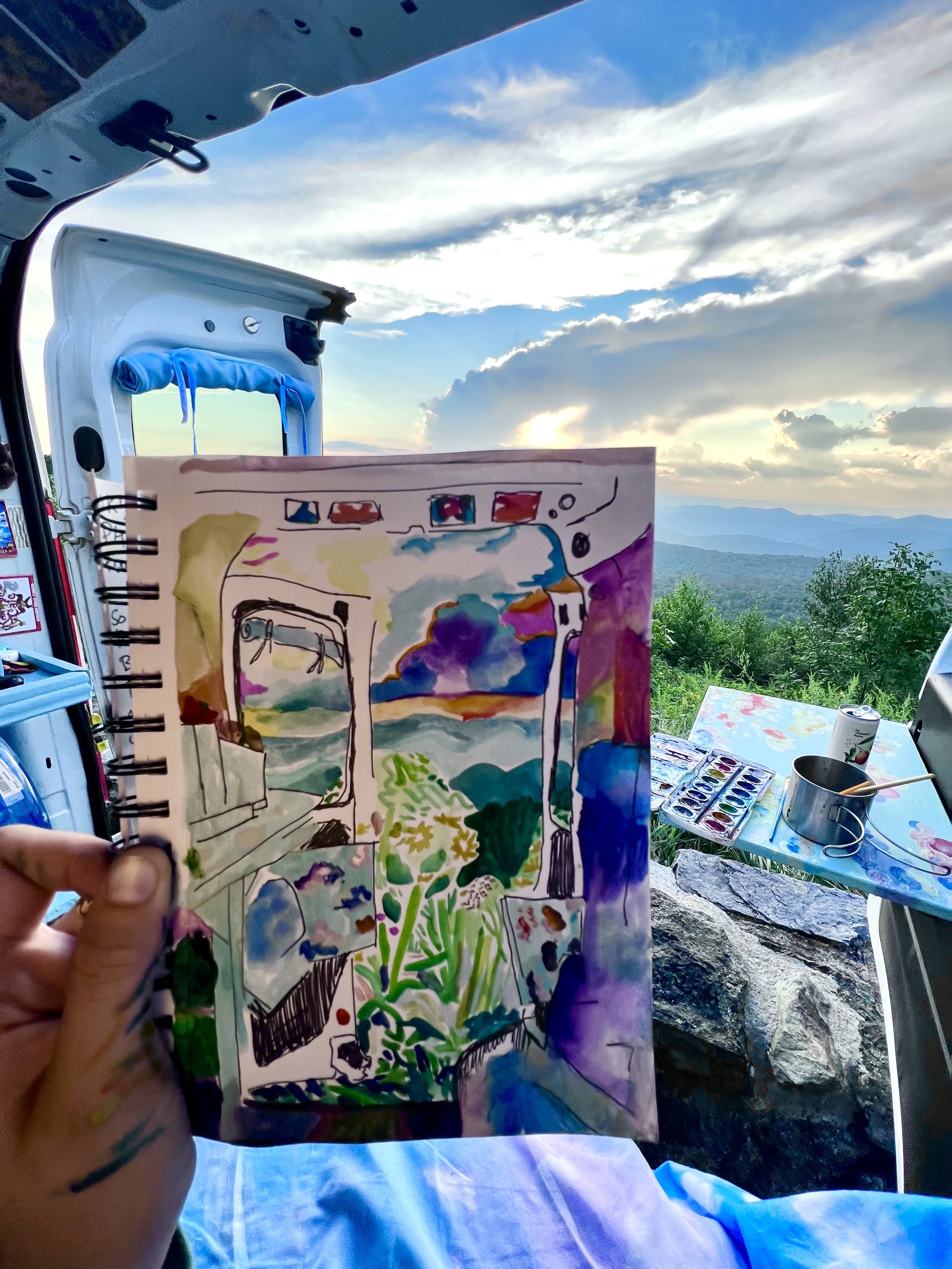

I knew it would be hard to leave New Orleans to begin graduate school in Savannah. I also knew that my love for getaways, festivals, and camping would continue to grow with my new surrounding geography (and a more flexible school schedule). So, in February of 2022 I purchased a campervan!

I did my research by renting a campervan and doing the most amazing Pacific Northwest trip with my best friend — (copy our trip here)! I LOVED the experience of traversing landscapes, keeping my belongings on me, and the freedom of exploration.

Over a few month, I spent some time customizing my van. Primarily, building out new woodworking and theming the van into a cotton-candy pastel paradise. ‘Poof the Pastel Puffer’ took shape and we hit the road in July to rack up 10,000 miles of adventures before I started at SCAD that fall. We’re now on 30,000 miles and counting!

Working on the van taught me so much about efficiency planning. While it often felt like 3-steps-forward, 2-steps-backward, I have never loved anything more. A couple of my top tips:

Make it modular — this modular “grid wall panel” setup allows me to clip in storage without heavy cabinetry and also allows me to strip down to a more aesthetic wall when I’m not doing a long haul.

Prioritize projects — I would have loved to paint my mural ceiling and add my dream light switch, but putting in the blackout curtains and situating the shelf storage was far more important before pushing off!

Experience the van while working on it — I extended the bed out when my friend joined me in the van for the Louisiana Migratory Birding Festival. That’s when I realized I set the table height wrong, preventing me from accessing my clothing stored underneath. It was frustrating to redo the table installation but necessary.

Lean on friends — so many awesome, talented friends helped me out by lending power tools and expertise. Attaching curtains with industrial velcro and bungee-ing my under-table storage cubes were perfect last-minute fixes when working on a limited timeframe

Make it home — the theming I did to make Poof my happy place delights me every time. The extra hours hand-painting clouds on shelving and staple-gunning cut-up fuzzy blankets were so worth it.

If you want to understand the DEEPEST parts of my spatial planning brain, check out this snapshot of my Google Maps. THIS is why I was an Urban Studies major at Columbia, and why I am so drawn to optimizing lived experiences.

Trip planning for a few days on the road! Some city stretches on the upper left. On the bottom right, Shenandoah pins point to campsites, vineyards, and trailheads at my fitness level (no 10 mile hikes please!).

Laying out a pit-stop in Pittsburgh. I love that these Google Maps listings lets me estimate distance, cost, ambiance, and menu before I select where to go to next! I can easily take recommendations out from text messages onto a mapped visual.

The chaos that ensues when I live someplace!

I have spent a lot of time researching trips/cities, and it would delight me if others would benefit from these efforts.

Some of these are several years old, so do double check these places are still open. Check out some of the trips I’ve planned in the past, below, and reach out if you have any questions or feedback!

Below is a section that shares more about my experience studying abroad in India, Brazil, and South Africa. While not part of more recent van life experiences and odysseys, I think it is an earlier glimpse into my draw to community, sense of adventure, and love for academia.

The IHP Comparative Cities program sends Urban Studies majors to spend 5-weeks each in Ahmedabad, India; São Paulo, Brazil; and Cape Town, South Africa. In each location, we complete independent research and engage in homestays.

The academic curriculum is combined with fieldwork involving key actors and stakeholders — public agencies, planners, elected officials, NGOs, and grassroots organizations. We spend time in different cities across the globe to better understand the interconnected social, physical, economic, environmental, and political systems affecting urban environments.

Though human needs may be similar around the globe, why does a city's ability to satisfy those needs vary?

How do people create a sense of place, of community, of urban identity?

What historical and sociocultural contexts frame the opportunities, constraints, and uncertainties of urban life?

What must be done — and by whom — to move toward ecologically sustainable cities?

What are the opportunities for political action by individuals, community organizations, social movements, and local governments to shape city life?

On the active Tumblr I have posted videos and images collected from my travels, quotations from interviews, blog posts, as well as post a series of podcasts from the field.

Jain temple in the Old City

~candid~

Ahmedabad Old City architecture

These old homes are recently undergoing a trend of historical preservation, adapting to become trendy bed and breakfasts

Ahmedabad Old City architecture (Jain temple)

Spicy

2nd largest mosque in India

Private tour of Hudson Yards was truly insane. We’ve been talking about housing insecurity all week from a social justice standpoint, seeing the terrible conditions of NYCHA apartments, but also learning about the complexities of managing properties on an impossibly small budget with demand off the charts. Because the federal government no longer builds housing, units can only be created through band-aid solutions (such as 80-20) that do not solve the root issues of the market.

Places like Hudson Yards that spur major new-age development is the face of evil to many social justice advocates – huge private investment aimed at the rich and perpetuating gentrification. However, as Michael Samuelian told us, they are absolutely willing to supply affordable housing as deemed by law, but building units on site means that just a few people get ultra-lux apartments, whereas if instead they were allowed to build off-site, they could help 3 or 4 times as many people where the land is cheaper in Eastern Queens. It was an interesting argument in the philosophical debate of how to actually help people and meet the growing needs – for many, it was an ‘aha moment’ that exposed the logic of the right.

Other super interesting tid-bits were learned included information on psychographics, which basically breaks down consumer behaviors based on how we self-identify. The categories he used were more nuanced but below is a more general example:

They used this info alongside neighborhood value surveys like the one below to carefully craft exactly what a dream neighborhood would look like for a Chelsea resident making over $100k a year.

And that was another interesting facet: they are CRAFTING a neighborhood. From SCRATCH. This fact means that many of the negative consequences of large-scale development are negated, in particular, displacing residents and small businesses. The one business they did have to buy out was a McDonald’s… and the price they did to do it?

$152 million.

Yep. Insanity.

Another cool and thought-provoking piece of the visit was the emphasis on sustainability going into the building designs. The codes for greenness were too lenient by the standpoint of the developers, so they took the process much further, becoming entirely energy independent and doing other innovative things like reusing their own byproducts and waste.

Samuelian also filled us in on the planning details of everything from the observation deck, to retail occupants, to cultural amenities (including a center with physically moving architectural buildings), to transportation connections to the new equinox center, and pretty much everything in between.

He also walked us through park design details (which obviously I nerded out about hardcore). William H. Whyte guided a lot of the principles, including making all floor components sitting friendly heights. The park connects directly to the highline and is the middle piece between the 7 line extension and the highline (which is crazy). He also went over the technology they designed for $7 million which allows tree roots to grow out horizontally and cools the soil because the train tracks below do not allow for deep soil tanks.

“The sun will never go down in Hudson Yards.”

We had 2 hours to kill between our NYCHA site visit and our trip to the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Community Center, so we swung by the BK bridge

My, oh my. Did the NYC skyline show up for orientation today, or what?

The 26 essays in The Just City Essays respond to the question: “What would a just city look like and what might be the strategies to get there?“ They were written by architects, politicians, artists, doctors, designers and scholars, philanthropists, ecologists, urban planners and community activists, and came from 22 cities across the world. Write a short essay n which you respond to the same questions.

On September 17, 2011, the economic divide of NYC had reached its boiling point. Financial District’s Zuccotti Park — which was given to the public by Brookfield Properties after being granted a zoning exception — was flooded with by protestors who had, until that point, only worked the minimum wage jobs keeping FiDi running smoothly. The public had taken ownership over its gifted space and did not leave for six weeks. The ’99%’ were occupying in protest for less political corruption, income equality, more and better jobs, bank reform, student loan policies, and foreclosure alleviation.

But Occupy Wall Street was more than just a protest; it was the first major wars between the two cities. In 2012, Manhattan had the biggest dollar income gap of any county in America, in which the top 5% earned 88 times as much as the poorest 20% of the population. A 2014 USA Today article began with the opening “Sports car sellers and Hamptons beach house Realtors rejoice: Wall Street bonuses hit their highest level since 2007.” When millions of Americans lost their homes, life savings, jobs, and then had to foot the bill of the financial bailout, the CEOs of the investment firms rebounded in just a few years to their previous levels of wealth.

The city that existed in the shadows of such opulence did not experience an economic rebound. These residents lack access to quality education, affordable housing, or livable wages. They lived in a city where the American Dream had systematically been moved beyond reach. The rich had tried to distance themselves from the urban blight and struggle of the poor for decades. As Cecilia Herzog illustrated: “There is a factor that plays an important role in many societies: fear. Security comes first, and what is the response of frightened urbanites? Divide the city! Divide the landscape! Live in ‘safe’ gated developments. The market loves and uses this fear in its favor,” (80). This fear literally created a second city in its division — one that was established by the federal housing agencies of the 1960’s who used racial redlining to prevent mortgages and halt any neighborhood investment. The legacy of such policies have only been aggravated, as William Julius Wilson notes that impoverished people of color are continuously shut out of major economic and social systems because of a mixture of covert racism, unconscious racism, institutional racism, and environmental racism, where traditional routes to ‘the good life’ are out of reach. As a result, separate — often illegal — systems arise because of lack of opportunities of advancement and neglect by elected officials.

The unjust city emerges when these two cities of polarized wealth and power cease to overlap. The alienation is extremely prevalent in urban divisions throughout the world. However, this schism need not be so dramatic, for all urban (and planet) dwellers long after similar ideals: to be surrounded by people they love, to be able to support oneself to eat and have a roof overhead, to feel safe and to learn. These goals are what unite us as humans and should be used as pillars in explaining why we enter the chaotic social contract of urban existence. However, when we have two cities, offering vastly disparate opportunities for advancement, we have a social contract that has failed our general will and failed its citizens. Therefore, the just city can be defined as a single, unified place capable of granting equal access to opportunity for its entire people. A just city means the American Dream can be within reach for all. We need a melting pot that actually oozes together.

As Lesley Lokko explains, “cities really are ‘collaborative works,’ places where people of differing racial, linguistic, religious and economic backgrounds and persuasions come together to enact some form of public (and private) life,” (12). We need to create an equal city by design — one that has cooperation to meet the collective goals of the general will. Marcelo Lopes de Souza states: “A just city cannot be a city where some of its districts and neighborhoods (call them favelas, ghettos, barriadas, villas miseria, callampas, townships, bidonvilles… ) are stigmatized just because the people who live there are dark-skinned or belong to an ethnic minority. If the city is the place of encounter and dialogue par excellence, then segregation and intolerance cannot be compatible with a democratic city,” (39). From Brown v. Board of Education we learned that separate but equal does not work and is inherently unjust. We need to have mingling of people from all backgrounds to secure the vivacity and innovation of urban life, and we need a single, unified city to set the stage for sustainable growth.

So, for this reason, we must have more confrontational spaces like Zuccotti Park. Ones where the status quo can be challenged and one city must confront the urban struggles of the other. Classes, political groups, races must recognize each other in order to inspire our best humanity, culture, and democratic system. Social inclusion can go a long way in uniting to form a just city. We need to come up with complementary agendas that holistically address the trap of poverty in a sustainable way.

We need transportation that can affordably and reliably connect all to the resources and benefits of the formal economy. We need livable wages and practical training to get people high-demand jobs in industries with labor gaps. Affirmative action can work to correct the wrongs of systematic racist legacies. We need fair security and court systems that truly operate on the notion that “justice is blind.” We need early education, reformed curriculums, competitive teacher recruiting, and access to higher education for all. And we need these shared, confrontational spaces to inspire involvement and garner feedback in designing and marketing programs for all of the above.

We need community ownership to drive participation. Residents must actually vote to get policies that will reduce economic barriers of entry, rather than maintain the status quo of having only 24% of people vote for mayor. And once the sense of inclusion is established and voters turn out, we need the democratic process to elect officials — from various walks of life — capable of representing their constituents.

People opt to live in the urban social contract to gain the benefits of communal living — innovation, opportunity, community — and when they do so they should be entitled to the benefits and collective goals of the system — shelter, economic opportunity, to support themselves and their families. When only one city reaps the benefits while the other is pushed to the urban fringe, we have injustice, a systematic cycle of neglect, and asymmetries of power and wealth. We need to unite, as one city capable of fulfilling the promises of the general will. Give everyone from a Wall Street Banker to a single mother from the Bronx a fair shot at life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

With Rio off the table for my one-week vacation, I’ve got my eyes set on Iguazu Falls

Iguazu Falls/Iguaçu Falls

The photograph says it all. Iguazu falls, one of the most beautiful sights that can be seen on our magnificent planet. A waterfall so beautiful that during her first visit, Eleanor Roosevelt said, ”Poor Niagara.”

India in 1760

First Pre-Departure Reflection: The Christmas Gift

House from 18th century - Santana de Parnaiba, Brazil

Elephanta Caves is one of the places I’m most excited to venture to