Architecture DESIGN AND VISUAL CULTURE

This design studio course introduced design as an analytical, representational and productive act. Emphasis was placed on the development of a methodology for architectural design work and critique. Students explored various analytical, conceptual and design approaches and examined existing and potential spatial and programmatic conditions. Students used and experimented with various modes of representation (collage, sketching, orthographic drawing, physical models). Students were encouraged to address architecture through the expertise of their own disciplines. Studio work was integrated with field trips throughout the city.

PROJECT ONE: NEGATIVE SPACE

The objective of project one was to build the negative space between a body part and two surfaces. I decided to build the area around my neck against a column and floor. First, I took photographs to see the space. Next, I built a mock-up in Model Magic that would help visualize the spaces that I could not see. Using this information, I built the model out of chipboard as my first architectural model. Finally, I did a section drawing of the model on parallel rule.

PROJECT TWO: PALEY PARK

Paley Park is a pocket park located at 3 East 53rd Street in Midtown Manhattan. Our assignment was to track a social function of how the park was utilized by its visitors. I visited the park multiple times during lunch, recording the arrival and departure times of each visitor, along with each visitor's gender and activity. I created a photoshop file to display the collected information. I then analyzed the information to build different mock-ups of how to redesign the space to affect the function of time.

final project: armistice

This is the final result of the Paley Park project. Below is the architectural statement alongside the final presentation materials.

When I first sat down in Paley Park, I was taken by the mindfulness of the people around me. People entered off the chaotic Midtown streets for different reasons — to listen to their music, smoke, eat their lunch in quasi-nature, meet a friend, or rest weary MoMA feet. Some stole just a few precious moments and others seemingly had no place else in the world they had to be. I was curious how table location dictated duration of stay and noticed the closer one was to the waterfall, the longer the stay. Towards the street, people (large groups in particular) filtered in and out without much introspection.

In this installation I wanted to embody the allure of Paley Park: the natural and calm oasis that seemed to be a reprieve from the urban battleground. The landscape would mirror the three zones in it’s complexity — the interior portion of the park would require more traversing, but would be rewarded with more isolation and scenery. The exterior portions would accommodate quick turn-arounds, while still integrating them into the overall park style, the western portion being slightly more complex for visitors who stayed a median portion of time. Lots of flexible, low seating accommodates groups, individuals or couples. The rises and falls of the topography is meant to cradle visitors in the natural environment they have grown alien to, and, in doing so, increase mindfulness and encourage sitting still, even if just for a moment.

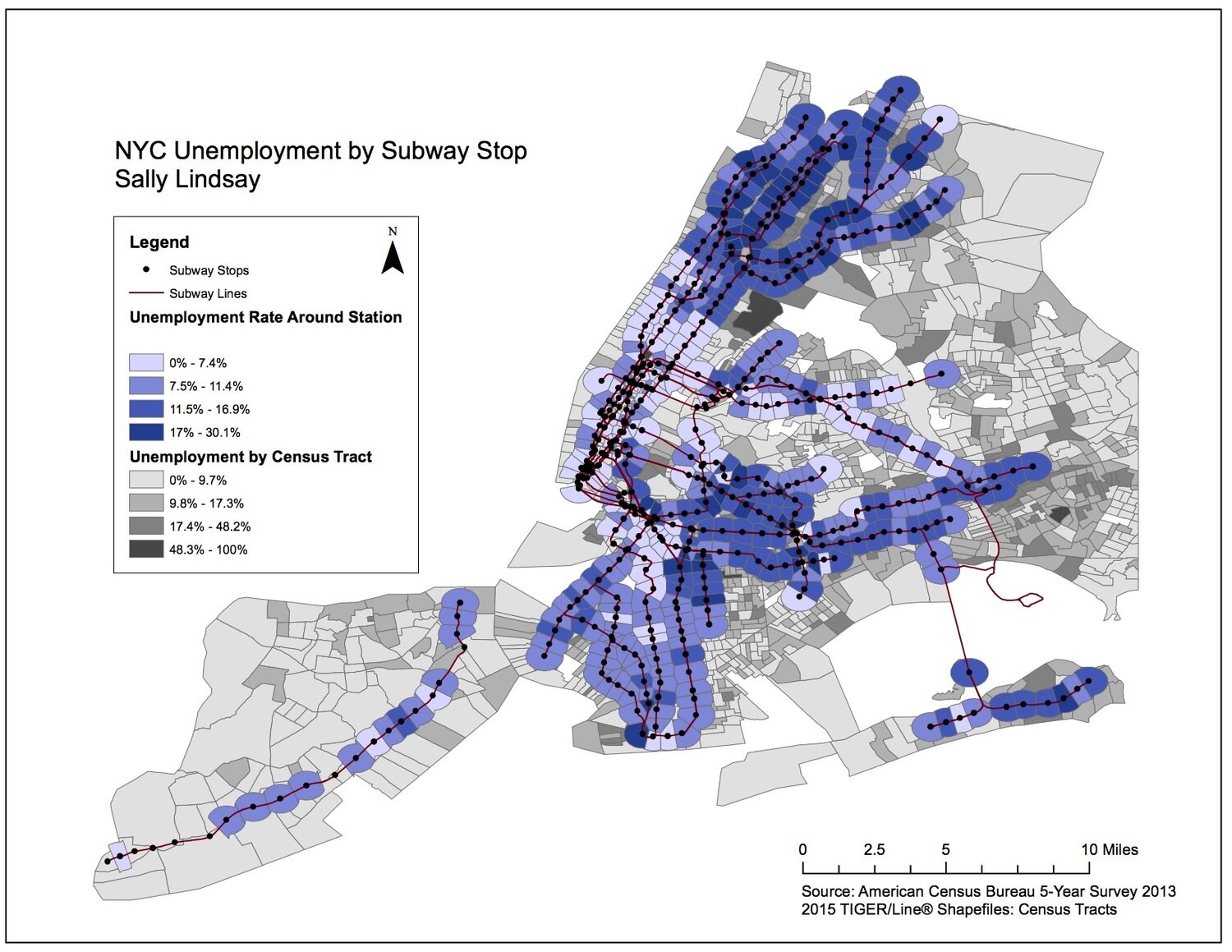

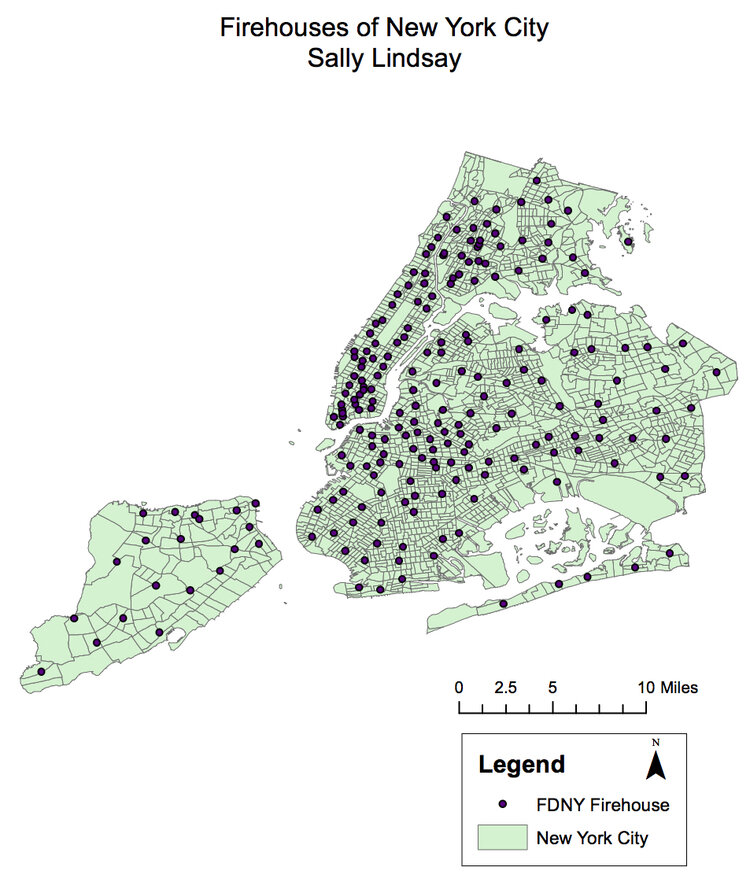

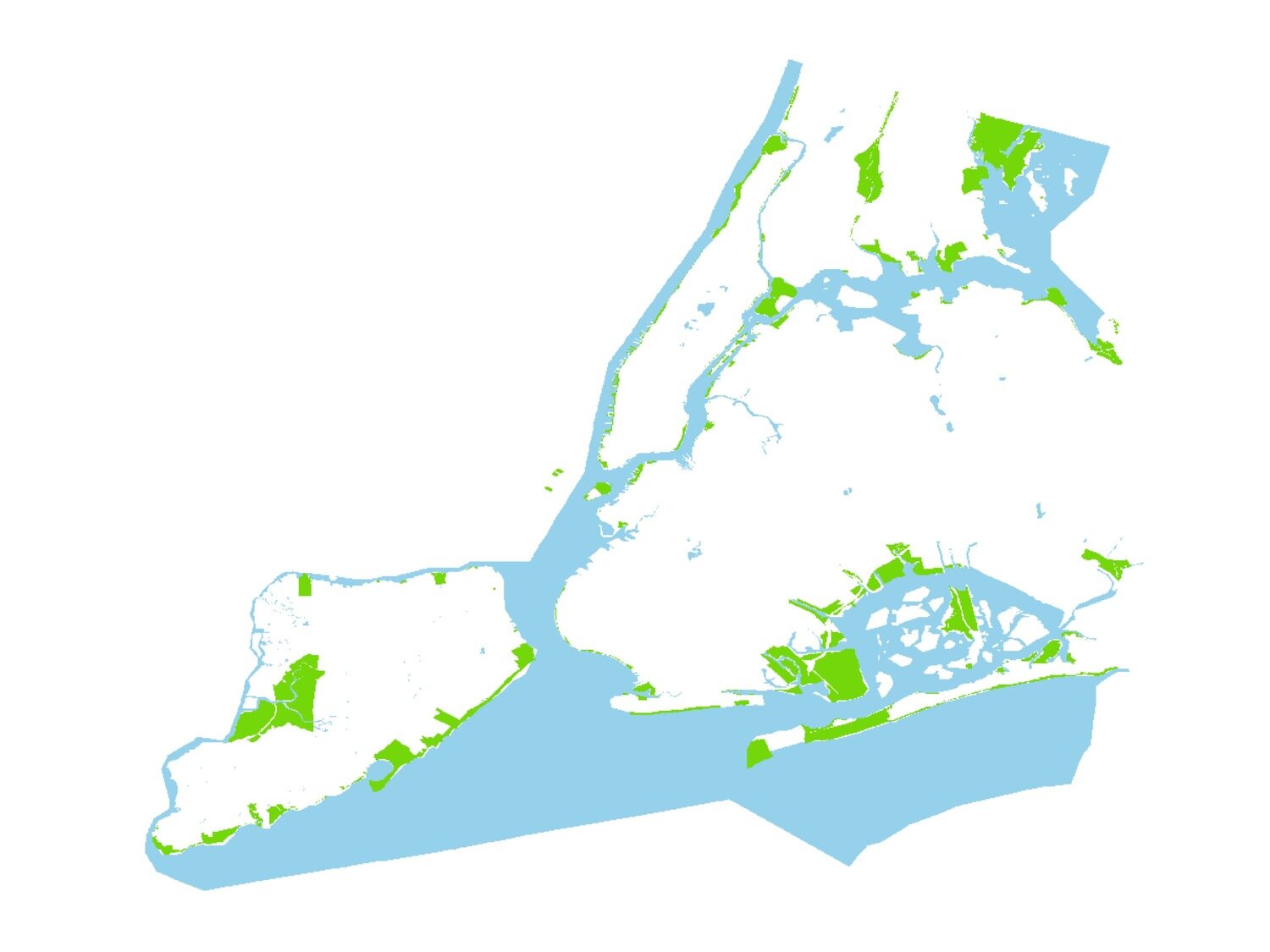

GIS: METHODS & CASE STUDIES:

We used state of-the-art GIS (Geographic Information Systems) mapping and analysis software to apply quantitative analytical methods to real-world urban issues. The course covered applied statistics and also included case studies focused on subjects like environmental justice, voting patterns, transportation systems, segregation, public health, redevelopment trends, and socio-economic geography. Over the semester we primarily used ArcMap, but also used QGIS.

The teaching objectives were as follows:

Identify (and if necessary construct) variables that measure something whose spatial variation is important to an urban analysis;

Use GIS technology to show spatial variation of important urban variables with clearly understandable maps;

Use GIS technology to make simple analyses of spatial relationships;

Use maps and spatial analysis to support an argument in urban studies;

Critically evaluate maps and map-based arguments on urban topics in both scholarly work and journalism.

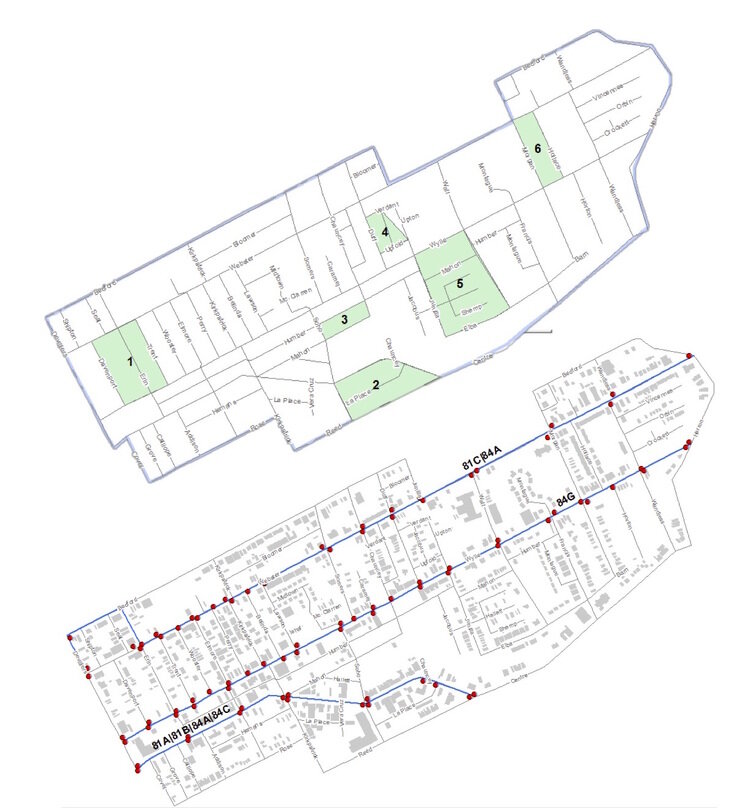

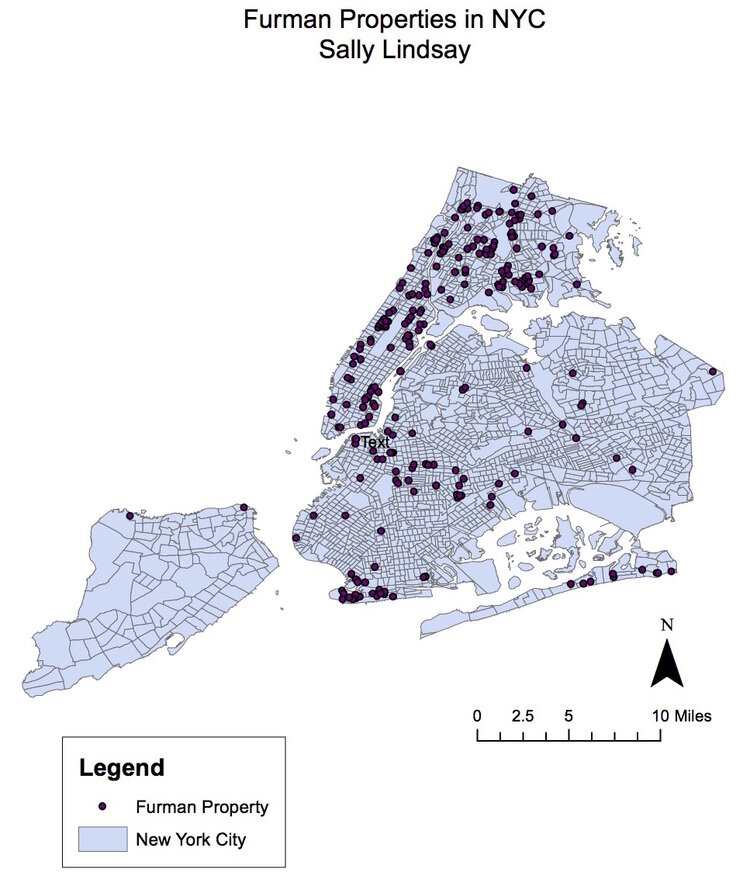

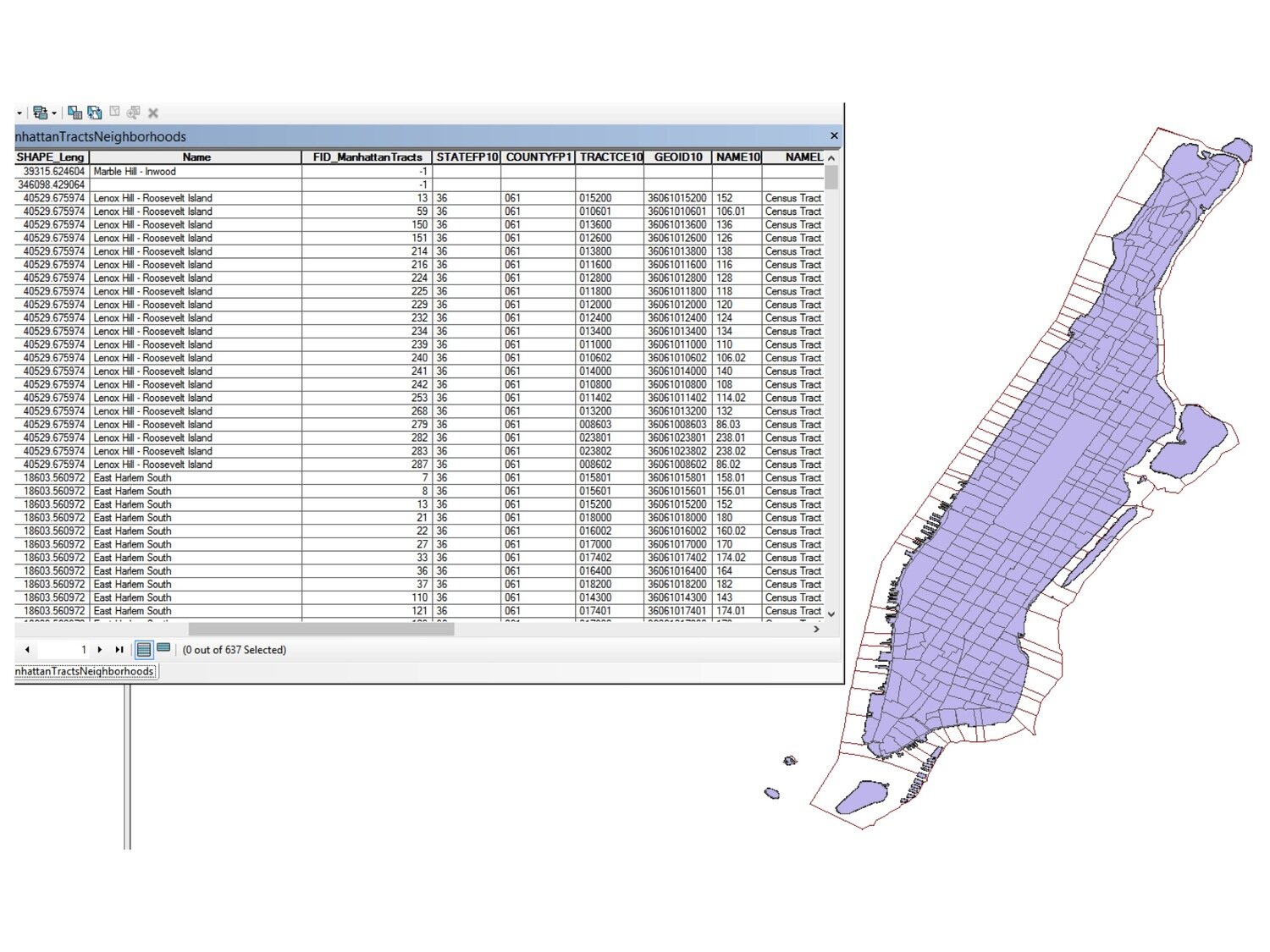

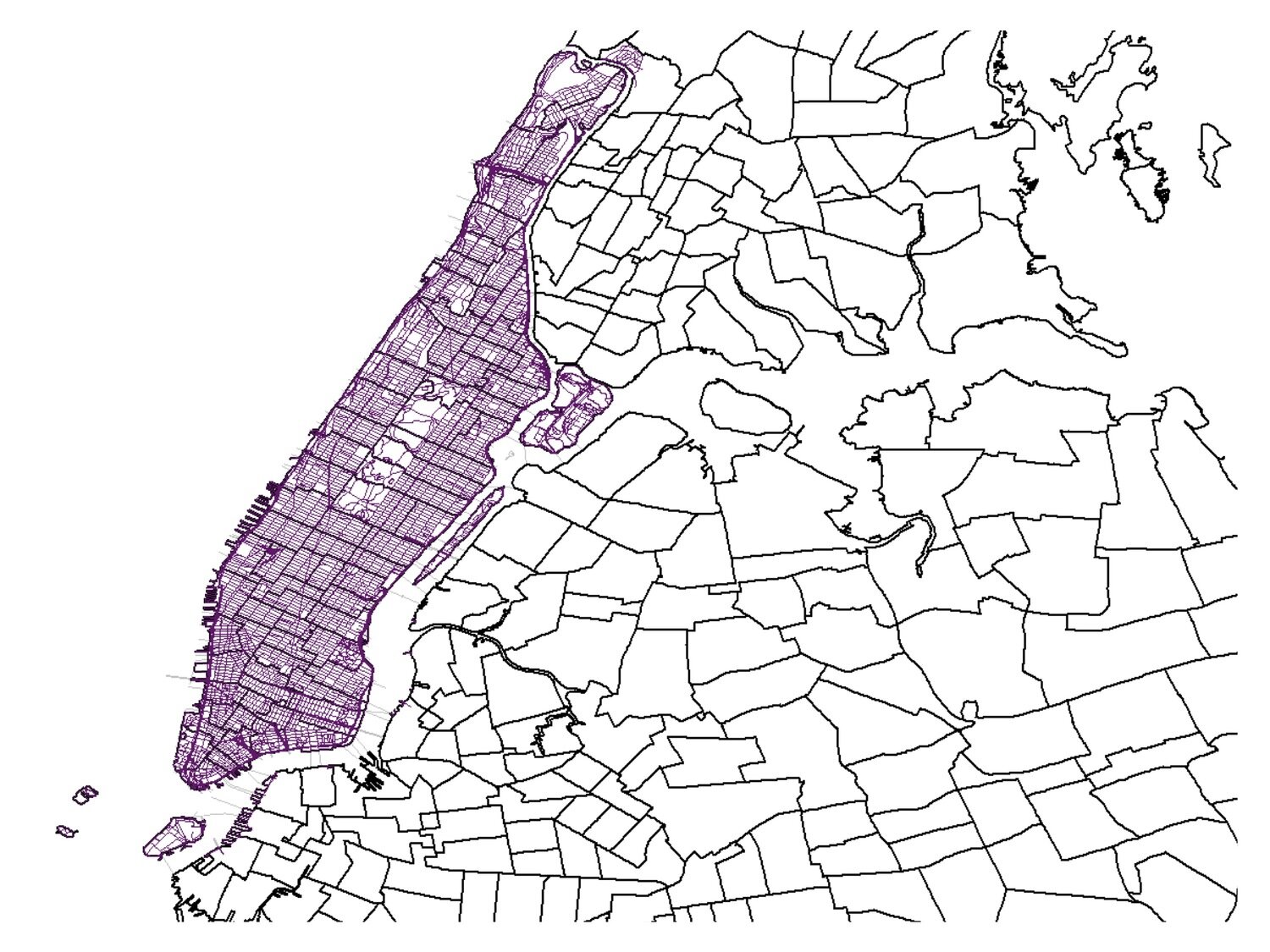

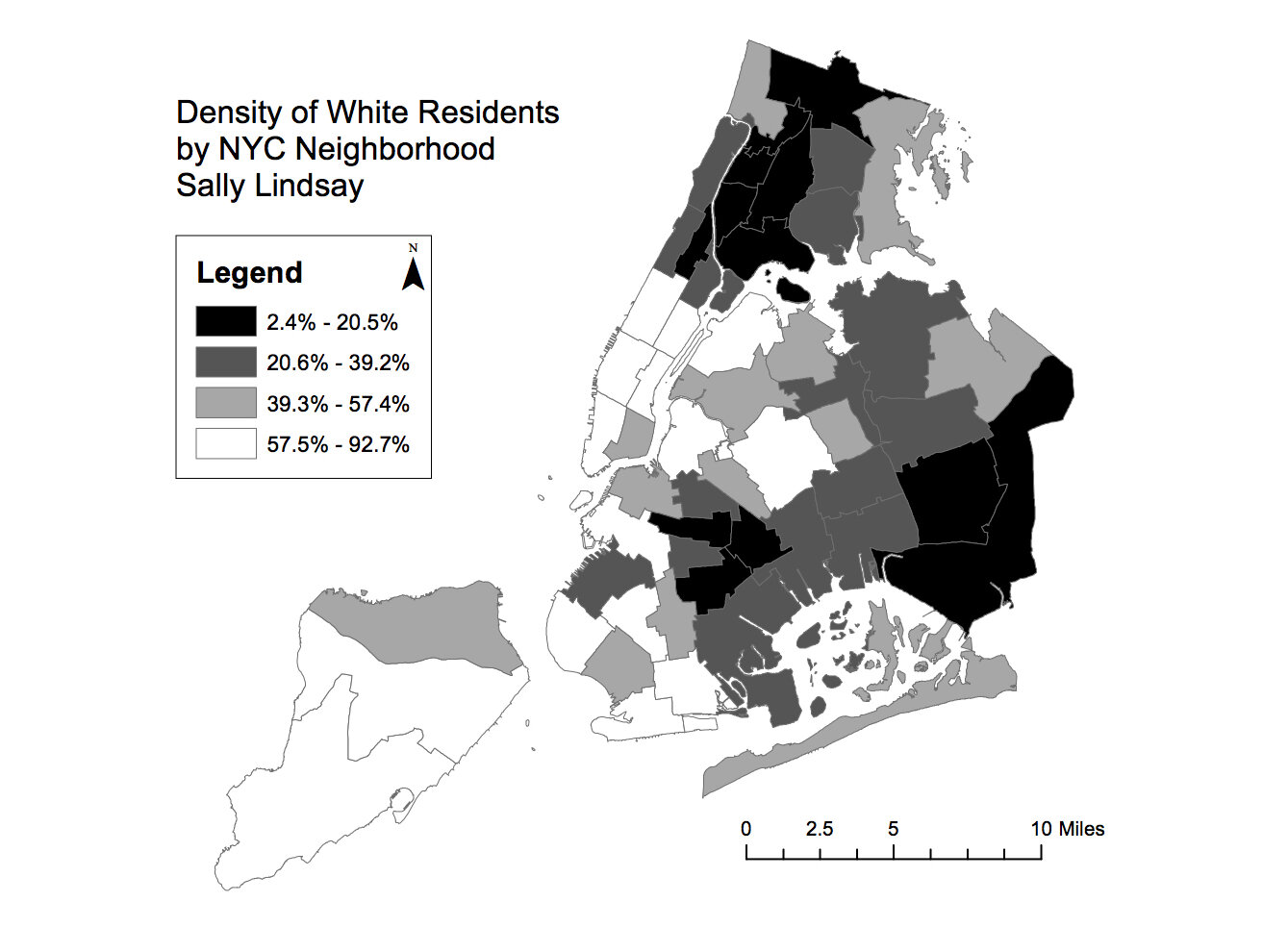

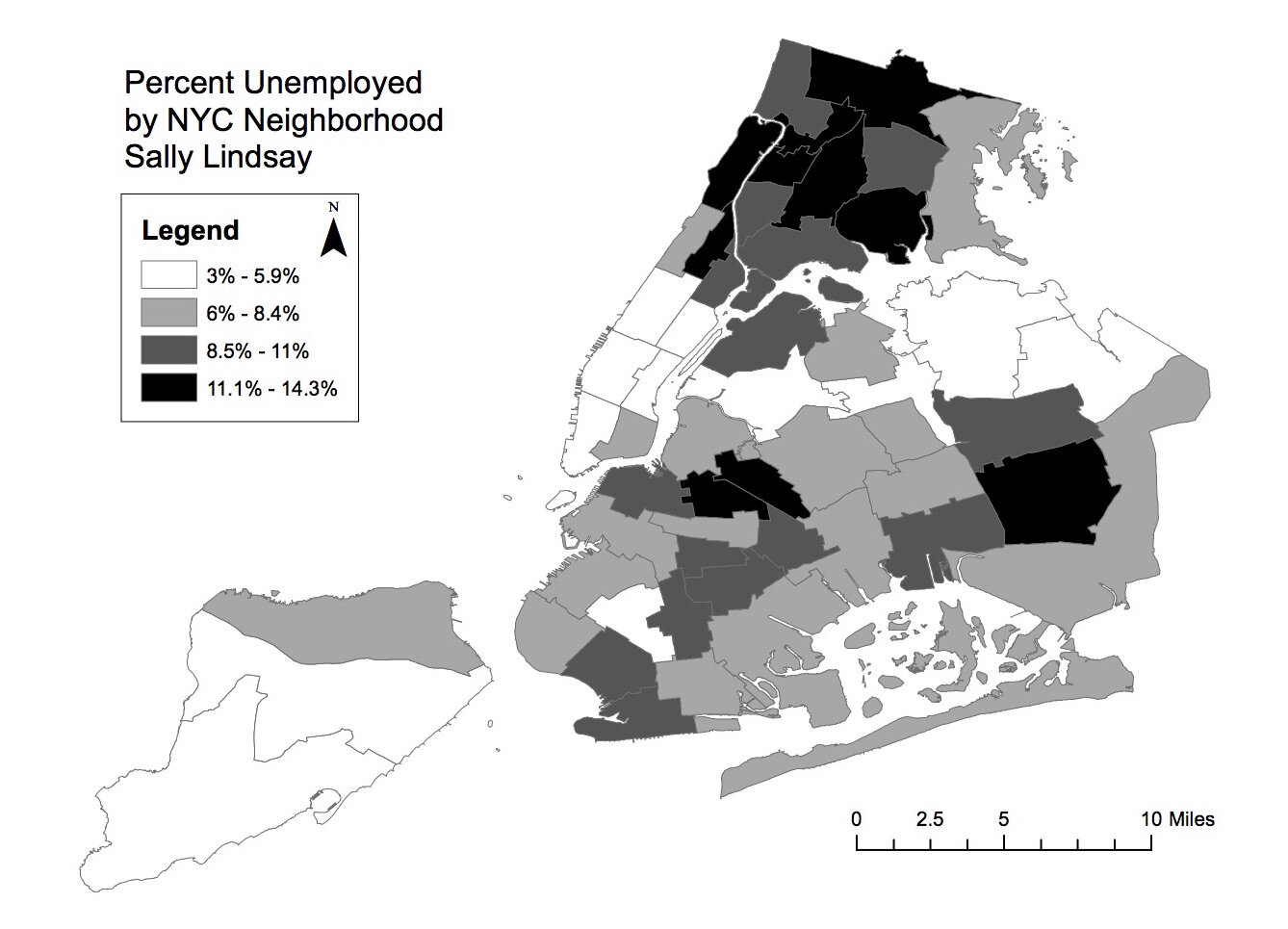

BELOW ARE MAPS MADE IN LAB SESSIONS

Term Paper: GETTING THE GRAFFITI OUT THERE

I. INTRODUCTION

Graffiti is a common sight in almost every city in the world. Graffiti has been around for as long as we have had walls; some graffiti could be found in Ancient Roman catacombs and in the ruins of Pompeii (Farrell). However, the first modern spray-paint graffiti began in Philadelphia and gained prominence in the mid-1900s with the rise of gangs in Los Angeles and Chicago (Farrell). Graffiti took off in New York in the early 1970s.

During this time, graffiti ran wild in New York City, particularly on subway trains, which were plastered with spray-paint throughout the interior and exteriors of cars. NYC across the board was in disrepair and Mayor John Lindsay set out to crack down on crime with a ‘zero-tolerance’ policy. He began by re-classifying graffiti from a nuisance (like loitering) to a crime, punishable by jail time and fines (Mars). The MTA attempted to fix the problem with barbed wires, ineffective ‘graffiti resistant paint,’ and police dogs, all of which, graffiti artists adapted around (Mars).

David Gunn became President of the NYC Transit Authority in 1984 and launched the “Clean Trains” program. He repaired every single train from the system and if a train car was found any graffiti, it was pulled from the system immediately, even if the tag occurred during rush hour (Mars). By 1989, the aggressive attack on artists proved successful as the trains became clear of street-art and victory was declared by the MTA (Mars). However, a consequence of this lost type of canvas was that artists moved back onto the street with serious force. The learning moment from the “Clean Trains” movement was that artists, first and foremost, cared about having their graffiti seen by the public. Once the MTA implemented its ‘zero-tolerance’ policy, the risk grew too high for artists with very little enduring reward (since the tag lasted mere minutes before being cleared).

II. PSYCHOLOGICAL MOTIVATIONS OF GRAFFITI ARTISTS

This victory pointed to the psychological motivations of graffiti artists that are still relevant for dealing with street art in our modern time. Graffiti on the streets today is now detached from gang culture (with gang graffiti accounting for only about 10% of tags) (Farrell). Instead, it is seen as a social sport. Many artists pursue the goal of “All City” meaning that ones’ tag is visible in a large area, thus marking one’s territory (Sirback). The reasons for engaging in this illegal activity vary and can be explored via a Reddit thread in which the initial poster asked “People Who Graffiti: Why?” Answers varied (UnholyDemigod). One online poster saw it as getting even with corporate culture:

“Look at every object. Its covered in corporate logos and registered trademarks. So you convince yourself that the whole world is tagged, anyway. So you think to yourself ‘f**k it. This is my world. Not Visa. Not American Bolt. Not Swisher toilet systems. This is mine.’ So you convince yourself that you're tagging to reclaim society.”

Others seek out street art as a way to feel connected to others:

“In hindsight though, I think it was more of a social networking thing. Taggers learn to recognize each other's tag, and who each other is. So you tag phone booths and restaurants and the bathrooms in bars. And then when you run into other taggers they're like ‘oh man I saw you way across town.’ Or you see their shit and you think oh, so and so was here.’”

Some see it as a powerful tool in combating the bleakness of neglected urban space — a public service intended to better the world:

“I grew up in the 5th most economically depressed city in the US. For my friends and I there was never any malice or destructiveness behind it, we just tried to add a little color to our bleak surroundings. The self expression helped to displace a lot of our negative feelings, more than anything, it was a release. I honestly never had any moral issue with it, and I still don't. Graffiti is artwork, it's one of the truest forms of self-expression, and I've always thought it was beautiful.”

Another poster said he did it for the adrenaline rush, the “Batman” aspect of it in which he had to hide his secret second identity; he craved the “narcissistic element of seeing [his] pseudonym” up in tags (UnholyDemigod). A lot of the pieces that go up are not like the glorified murals that are becoming increasingly trendy with the gentrification of urban spaces. The tags are scrawls, initials, or other unsophisticated tags. One user describes the motivation (UnholyDemigod):

“It's about self worth and self-purpose. Fantastic murals have aesthetic value and take skill. However quick throw ups like Tag09 are a different story. You have nothing worthwhile, you have no friends, hell you're even bored, but when you tag all of your worries and problems are gone. The only thing you're concerned with is getting your tag up and being smart about it. Your tag is everywhere. People see it out of the corner of their eye and you know they see it. They know who you are by your tag. They might see it once a day or once in their life but they saw it, they saw you. You might not have much but you have your tag. It's a way of life really that some follow in the pursuit of self validation. There's also a rush of individualism when you go out and tag. Your tag is solely yours and you own what you bomb. When you're out you feel that it separates you from everyone else. Everyone else is just going about their day and you just look like you are but meanwhile you're scouting out good places, or just walking around with a paint pen.”

These “quick throw ups,” though, are a continual nuisance. Shop owners and landlords must deal with the damage to their private property. The graffiti that goes up tends to compound itself because artists start to compete with each other and build networks of artists that seek out to conquer more and more territory (Walker). However there is one proven way to combat the onslaught of street-art, as illustrated by the power of the “Clean Trains Movement.” Paint is expensive, costing about $5 per can, and with some larger pieces taking up to 30 cans of spray, often in about 15-20 different colors, artists want to get the most bang for their buck by creating pieces with staying power (Farrell). Having officials quickly paint over the graffiti makes the endeavor a tremendous waste of both time and money and works as a deterrent for an artist to revisit a particular space (Kramer). This power can be leveraged by officials in order to quell scrawl, but requires precise targeting to see where their patrolling can have the greatest impact.

III. USING DATA TO TRACK AND COMBAT

Through utilizing the data from NYC’s 311 hotline, we can see which areas artists target most frequently in order to understand how to tackle graffiti in our city. We were able to map instances of graffiti reported throughout New York City. There were over 14,514 reports from 11/08/2014 to 11/08/2015. These data included information such as each incident’s address, police precinct, reported date, and status of clearing. However, with such a large amount of data, the data had to be randomized then sorted to select representative sample of 2,500 reports over the year, using that information to geo-process the incidents and map accordingly.

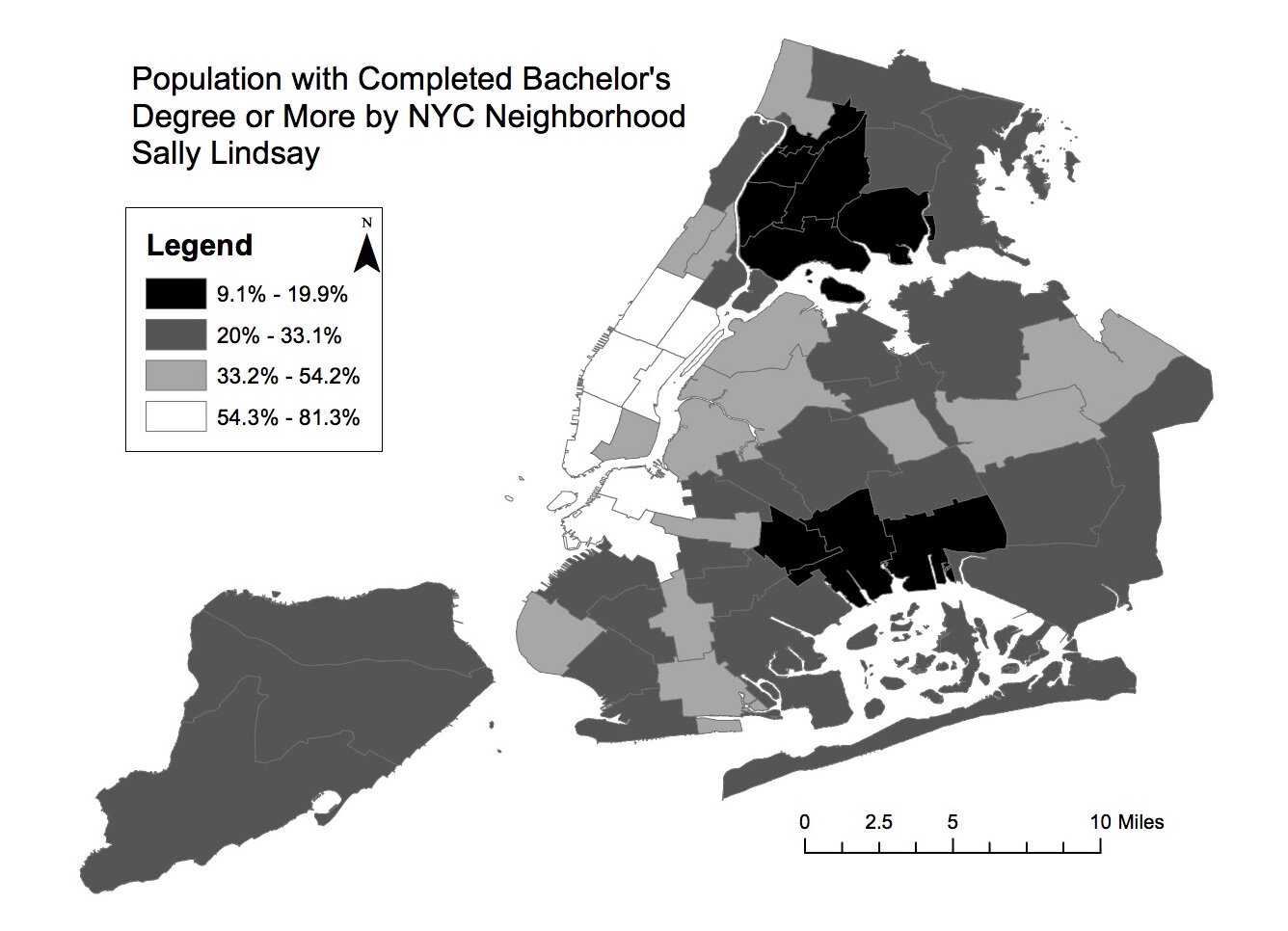

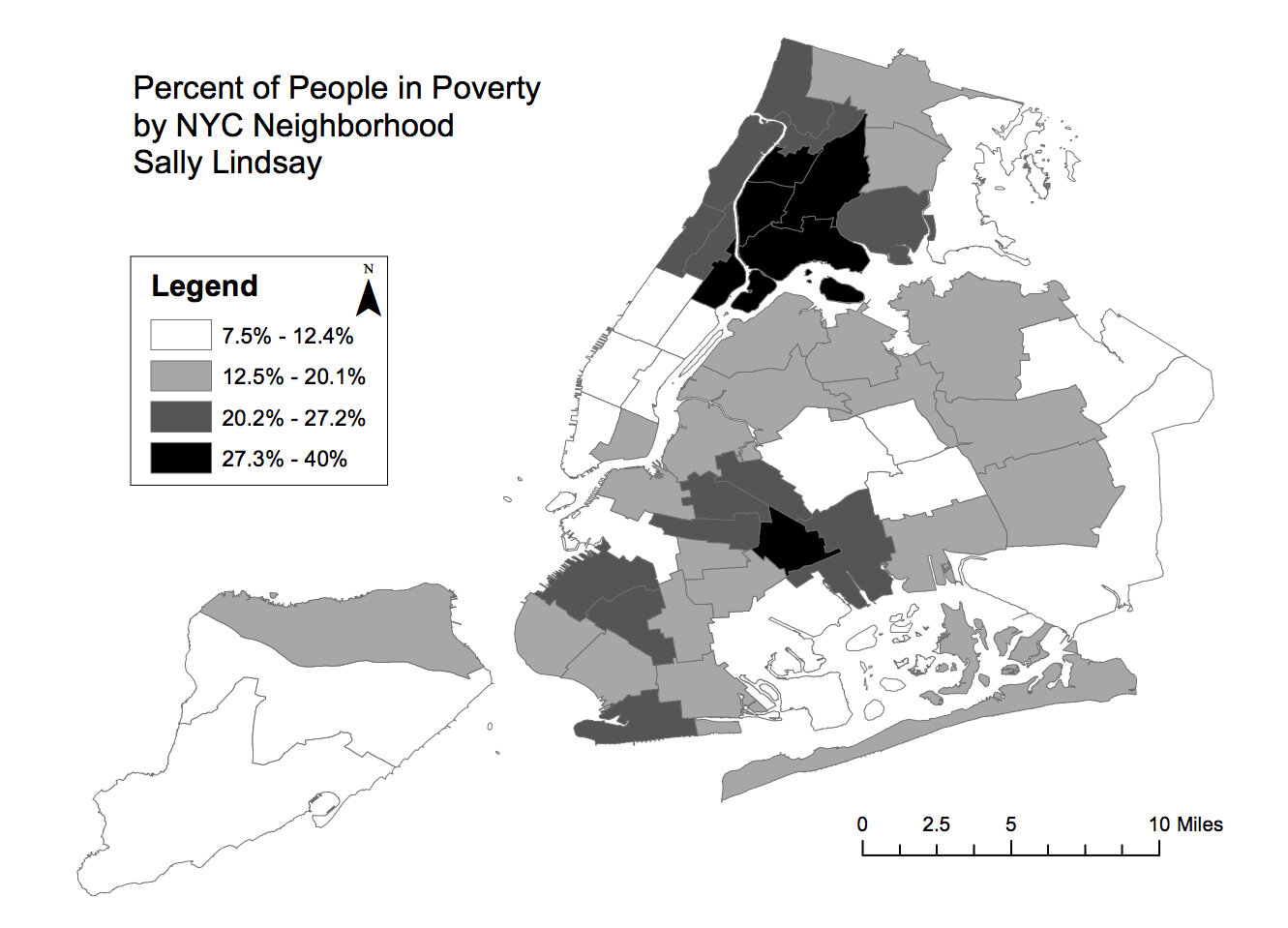

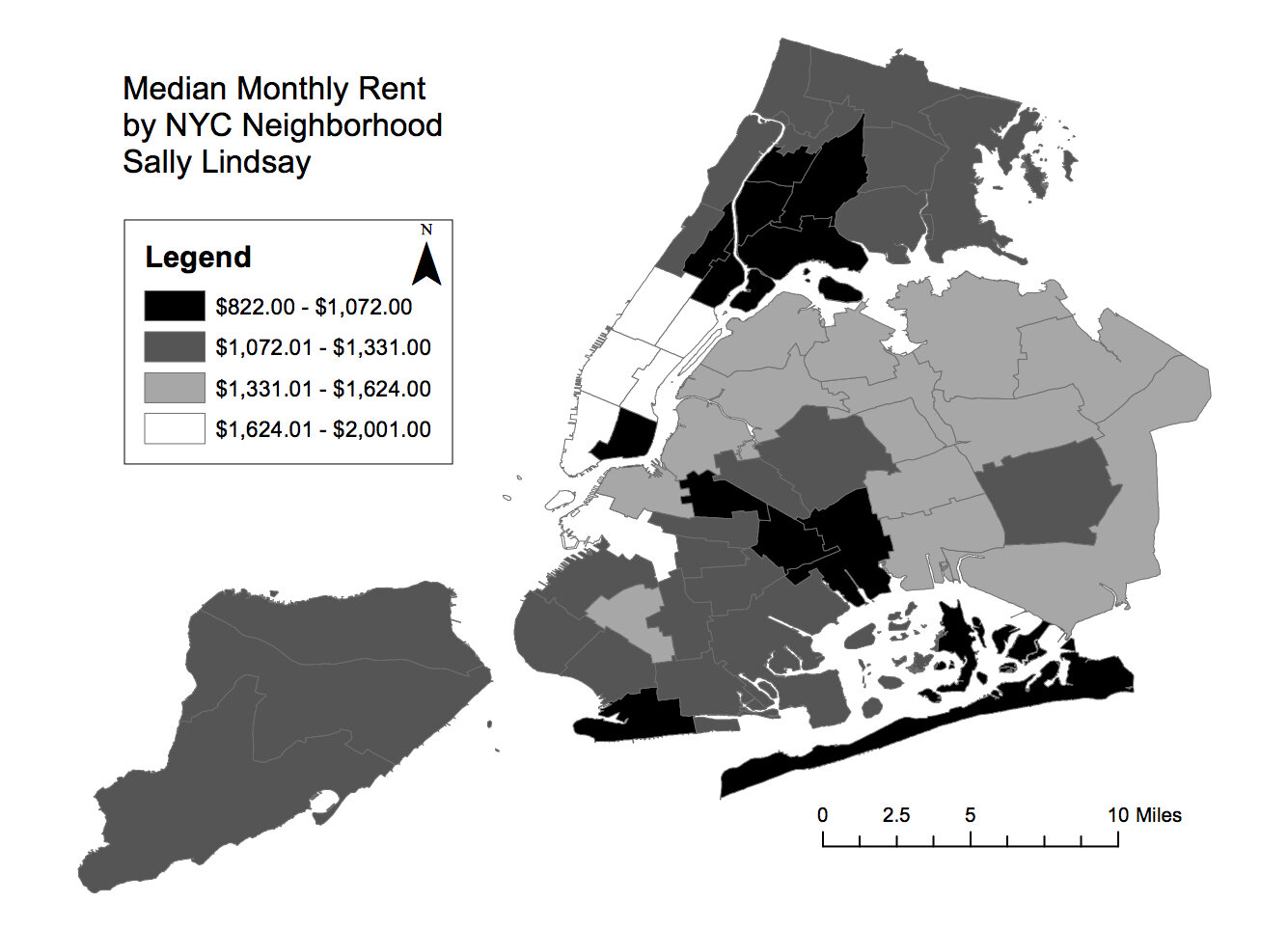

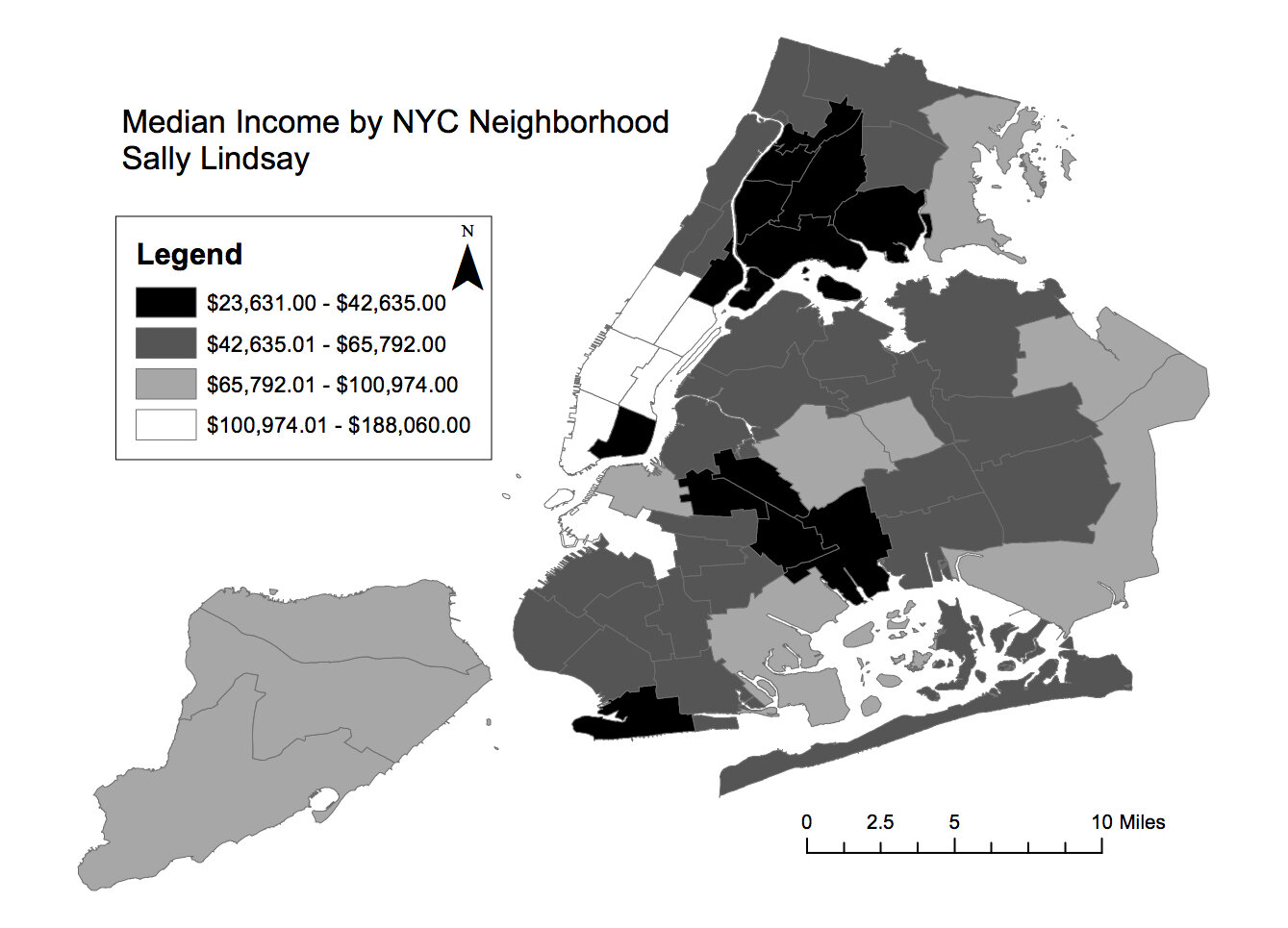

Areas that were targeted most were economically depressed. Poverty can exist as a trap, with many variables showing overlapping characteristics and trends. In mapping data from the U.S. Census Bureau, several variables were seen to have similar trends, including percentage of the population over 25 years old without a high school degree, the median income, median rent, unemployment rate, and percentage of those living under 18 years old living below poverty. All of these factors are correlational with directionality issues, preventing us from truly uncovering one defining issue of poverty in a neighborhood. However, with each factor we can explore potential explanations for correlations to better understand how neighborhoods in NYC vary and make some more vulnerable for graffiti than others.

Below are the results of the maps alongside analysis discussing the results of the maps. The social data collected from the census, though, all intertwine to prove a strong correlation between deprived neighborhoods and location of graffiti instances.

The first social factor explored was high school drop out rate. It is a common belief that graffiti (particularly tags and unsophisticated graffiti that has high likelihood of being reported) is often crafted by youth. The assumption that these youth may have idle time on their hands or a lack of responsibility that allows them to be out on the streets late into the night could be correlated with rates of youth poverty and high school drop out rates. Kids who do well in school are probably not out between 3:00 and 5:00am tagging walls. Kids who also have lesser accountability at home (perhaps who have parents working multiple jobs to have ends meet) are more free to roam around and seek companionship in communal networks with similar interests, like the graffiti artists’ groups. One poster on Reddit describes the cultural appeal and sense of purpose that comes from engaging in the illegal activity (UnholyDemigod):

I think most people get into writing from living in lower income urban areas as it's just what a lot of people do there. There's a community you can be a part of and it's a fun way to express yourself in a mostly healthy way… It was really fun. I mean, going out at night when the city is asleep and exploring with your friends and running from security guards is a rush. Eventually, if you do it enough and get good enough you'll get invited to all kinds of parties with new people and you'll meet all these cool writers that you see around town and they'll recognize you. It's awesome.

Kids who are running around all night long probably do not keep great attendance at school and thus might not perform well in the classroom. Based off of this assumption, we can map the relationship between high school drop out rate and graffiti, as well as poverty to see if the Reddit user’s reflection on lower income urban areas proves true:

The correlation between population without a high school degree and graffiti instances is particularly strong. The areas with very dense instances of graffiti also match areas with the highest percentage of the population without a high school degree (28.1-40.4%). These areas include: Sunset Park, Bushwick, and Washington Heights. The directionality of this claim is unclear, though. It could be that the children tend to not graduate because they are rebellious and tend to not respect authority. Or, it could be that kids who are not occupied with school turn to graffiti for a sense of community, purpose, and entertainment. Another possibility, kids who do not do well in school have a greater affinity for art, which is expressed through graffiti instead of formal art courses — a luxury not afforded to many poor neighborhoods.

Off this information, one would assume that summer months would have a higher number of reported instances compared to months where kids were in school. However, this was not the case, which suggests that youth who engage in graffiti operate out of the school year, further strengthening the potential tie between high school drop out rates in neighborhoods and street art.

Another subset of people who can feel neglect and disillusionment from formal society are those who are unemployed and not able to hold or access a job. The map below again shows we see a connection between factors, though the correlation is not as distinctly strong as it was for youth populations. This could mean that the stereotype of teenagers putting up graffiti could be more supported since the social factors of the adult population have less of a connection. But the social network affronted to kids may just as likely extend to adult populations who find themselves in street art crews with a newfound sense of purpose.

Another factor tied to poverty that yielded interesting result was the median rent of neighborhoods. Below is the map:

The study of median monthly rent is an interesting one, because rent prices can correlate with a neighborhood’s desirability and interconnectedness. People pay more to live in newer neighborhoods, and, as Barry Woods of Graffiti Control Systems stated, taggers tend to target unkempt two- and three-story buildings that are more than 80 years old and are not part of the central business district. (Walker). Rent would be higher in areas with new housing developments in neighborhoods that have more investment. Areas like Union Square and Times Square represent economic hearts of Manhattan with high rents, high density, and round-the-clock retail that would make it inopportune for tagging. Neighborhoods with low rents and/or NYCHA Public Housing (indicated in pink on the map above) — such as the Lower East Side, East Harlem, East New York, and Soundview — have lots of graffiti. Perhaps the areas with public housing have less land available for redevelopment or are seen as less desirable for new business, leading to older buildings that are easier targets for graffiti.

Median income for a neighborhood is even more clearly correlated to graffiti instances than rent:

The coastal neighborhood regions of Queens and Brooklyn reflect the relationship closer. A factor that could make sense in explaining the connection between higher median income and lower rates of graffiti could be political efficacy and power. Areas with higher property values could have doormen or greater access to the New York Police Department resulting in more “eyes on the street” to prevent crime and increase risk for graffiti artists. Street artist Schmoo explains that a single piece can take anywhere from 30-minutes to 3 hours depending on the quality standards of the artist, meaning that the risk of tagging goes up significantly in busy areas (Farrell). Additionally, areas with richer residents benefit from more NYPD surveillance overall to catch taggers in the act. Areas with greater poverty could be neglected more by patrolling officers, or, officers could be more worried about violent crimes than something as innocuous as graffiti.

As Dr. Jeffrey Chase, a clinical psychologist and professor at Virginia’s Radford University, explains: “Vandalism to me is basically anger. It can be displacement — displacement in the technical sense is that [vandals] wish to do something against a more threatening object or individual, so they vent their anger on something safer,” (Walker). People who feel neglected by economic, political, and social systems because of poverty seek an outlet for this outside resentment of inequality. A potential solution is to foster the creative impulses of residents rather than continue the cycle of neglect. Two potential solutions could include expansion for the Arts for Transit program and providing legal graffiti spaces.

VI. POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

The Art for Transit program attempts to beautify the drab stations of NYC transit by working with artists to install sculptures, ceramics, mosaics, and other installations. While the program currently works with mainstream artists, incorporating graffiti artists to commission wall areas would create a productive outlet that could empower artists to respect the private property they once defaced. In a study by Kramer, all 20 graffiti artists were in favor of public art projects and wanted to see more of them; some even pointed to the expansion of the Art for Transit program in particular. Two statements read (Kramer):

“The Arts for Transit program is cool. I wish they would try to find a balance with [graffiti] writers . . . I hope the generations that take control of these institutions aren’t so closed minded.”

“I myself can adapt to different mediums. I could deal with something like [the Arts for Transit] program, especially if there is a little money involved or some exposure. It’s just another outlet.”

‘Legal walls’ also offer an opportunity to allow for street art community to communicate and appreciate each other’s work — providing a more permanent canvas to celebrate art. They operate as public spaces that give temporary leases to artists on a rolling basis. Legal walls also elevate the quality of the art that would be posted, as artist Kairos explains: “The limited number of legal walls leads to writers constantly having to go over one another for space. This drives the better writers away because they do not want to see their time-consuming works trashed in only a matter of days,” (Farrell). With the recent closing of 5 Pointz in Queens, the only remaining legal wall in New York City is “The Graffiti Hall of Fame” on 106th and Park Avenue. Karios also goes on to explain that street art holds some potential for corporate sponsorship, as can be found throughout Australia, where big-name companies sponsor artists as a sport of sorts (Farrell).

Understanding which areas are most vulnerable to graffiti can be a powerful tool for law enforcement. Each instance of graffiti costs between $1-$3 to remove, which means New York City pays between $14,514 and $43,543 in just cleaning costs, not including the salary of employees. Using these data to understand the underlying correlations for graffiti offers a chance to combat the issue of graffiti via patrolling interventions, installation of legal walls, or media campaigns promoting more productive art outlets.

WORKS CITED

Farrell, Susan. "Graffiti Q & A." Graffiti Q & A. Art Crimes, 1994. Web. 22 Dec. 2015. <http://www.graffiti.org/faq/graffiti_questions.html>.

Kramer, R. "Painting with Permission: Legal Graffiti in New York City." Ethnography 11.2 (2010): 235-53. Web. 22 Dec. 2015. <https://www.academia.edu/5077315/Painting_with_permission_Legal_graffiti_in_New_York_City>.

Sirback, Thorne. "Why Do People Tag?" Examiner.com. N.p., 18 Apr. 2011. Web. 22 Dec. 2015. <http://www.examiner.com/article/why-do-people-tag>.

UnholyDemigod. "[Serious] People Who Graffiti: Why?" AskReddit. Reddit, 16 Nov. 2014. Web. 22 Dec. 2015. <https://www.reddit.com/r/AskReddit/comments/2mguth/serious_people_who_graffiti_why/>.

Walker, Benjamin F. "Graffiti Psychology: Why Vandals Strike." CleanLink. N.p., 1 Feb. 2004. Web. 22 Dec. 2015. <http://www.cleanlink.com/cp/article/Graffiti-Psychology-Why-Vandals-Strike--1131>.

Data courtesy of NYC Open Data: < https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/DSNY-Graffiti-Information/gpwd-npar> and the United States Census Bureau.